Blog...

A blog post is loading...

Jan 1, 2025

Loading…

A blog post is loading...

Jan 1, 2025

Loading…

A data-backed look at how Max explores v0 and what it teaches me about personal software.

Feb 2, 2026

In early December, my son Max asked me to help him build something on his iPad.

In the old world, I would have opened Scratch, explained loops and variables, and watched the energy drain out of his face halfway through. That’s not a knock on Scratch — it’s just not how kids want to create when the interface is talking.

So instead, we opened v0 (pronounced “v‑zero”), an AI app builder from Vercel. You describe an app in natural language, it generates code, and you get a live preview you can run and share.

This is the broader shift happening in software too. A lot of engineers are moving to agent-first tools like Claude Code and OpenAI’s Codex. I wrote a longer version of that shift in Coding in 2025: the interface stops being “type code” and becomes “tell an agent what you want.”

I wanted to see what happens when you give that interface to a seven‑year‑old.

Before I tell stories, here’s the denominator.

In this window (December 1, 2025 → February 2, 2026), there were 109 chats on this account. Of those, 106 chats generated at least one version (a runnable preview).

So this isn’t a few cute projects. It’s a real build portfolio: lots of starts, a handful of obsessions, and repeated iteration loops.

Here are a few of his favorite builds from that first month (tap to zoom):

He didn’t really need help. He typed. He spoke. He asked for what he wanted. When something broke, he kept going until it worked.

And he burned through credits fast — the free tier in a couple days, then my pro credits a few days after that. When his mom said I was allowed to buy him credits because “it’s educational,” I realized we were in a new era of parenting.

After about a month, I had a question I couldn’t shake:

What does learning look like when the interface is an agent, not a programming language?

So I exported the data and treated it like a logbook.

I exported chats, messages, and versions from v0, then fed the raw JSON into a coding agent directly to compute stats and help me sift the logbook.

Because this v0 account includes both his prompts and some of my early testing prompts, I tried to separate the signal from the noise:

I use two lenses in the analysis:

Two quick definitions:

Prompts per Week (Dec 2025 → Feb 2026)

700 with extractable text

~1.13 per prompt

Fri–Sun (418 prompts)

Busiest week: Dec 8, 2025 ( 177 prompts)

Fri–Sun: 58% ( 418 of 723)

What the scoreboard says:

So the behavior is: start fast, kill fast, then double down hard on the few that matter.

Showing the top 35 chats by prompt count. Chat titles are whatever we named them in v0; some include my prompts too.

Almost half his prompts are 10 words or fewer. He doesn’t explain; he issues directives:

It’s the language of someone who assumes the computer will understand intent.

61% (385/629)

Excluding the pasted error boxes, 385 of 629 prompts start with “make…”. He’s not describing implementation; he’s describing outcomes.

In this window, 71 times he pasted an error box (“the code returns the following error…”) and asked the system to fix it.

That’s not “I’m stuck.” That’s “next step.”

The headline: most of the time he’s just building. But roughly 1 in 4 text prompts are “friction” — debugging, getting the look right, making it work on mobile, or trying to publish.

That friction tax is where the most interesting product questions show up: memory, taste, and shipping.

He keeps having to repeat constraints that feel obvious:

I HAVE TO TELL YOU THIS EVERY TIME MAKE IT MOBILE

Across the window, he explicitly asked for mobile/iPad support 25 times. A new chat feels like starting over.

He’ll iterate on mechanics all day. What he hates is when the output looks wrong.

Across the logbook, he had 61 prompts that were explicitly about how things look (images, graphics, style) — almost as many as the 71 pasted error-box prompts.

In a Gumball project (the cartoon), he kept tightening the spec:

Taste is a requirement, not a vibe.

The AI Buddy project is where the future shows up… until it needs a link:

AI Buddy (55 prompts). The future… until you need a URL.

AI Buddy (55 prompts). The future… until you need a URL.

If you can’t ship, the toy doesn’t feel real.

And then the most honest version of this desire:

MAKE IT LIVE!!!!!

That’s the portfolio-level pattern. Now the interesting part: what those high-iteration projects were actually trying to do.

The most intense project started like this:

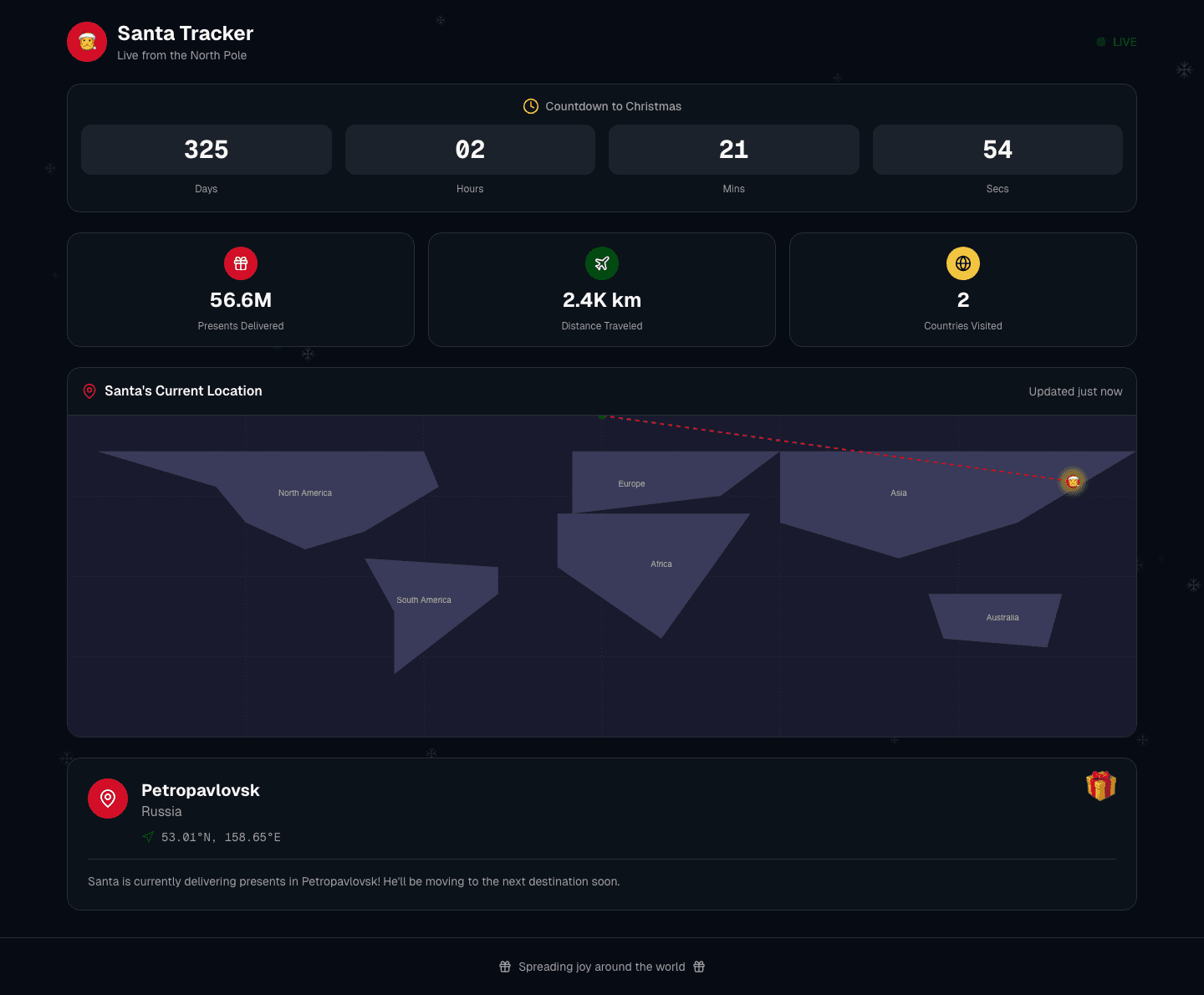

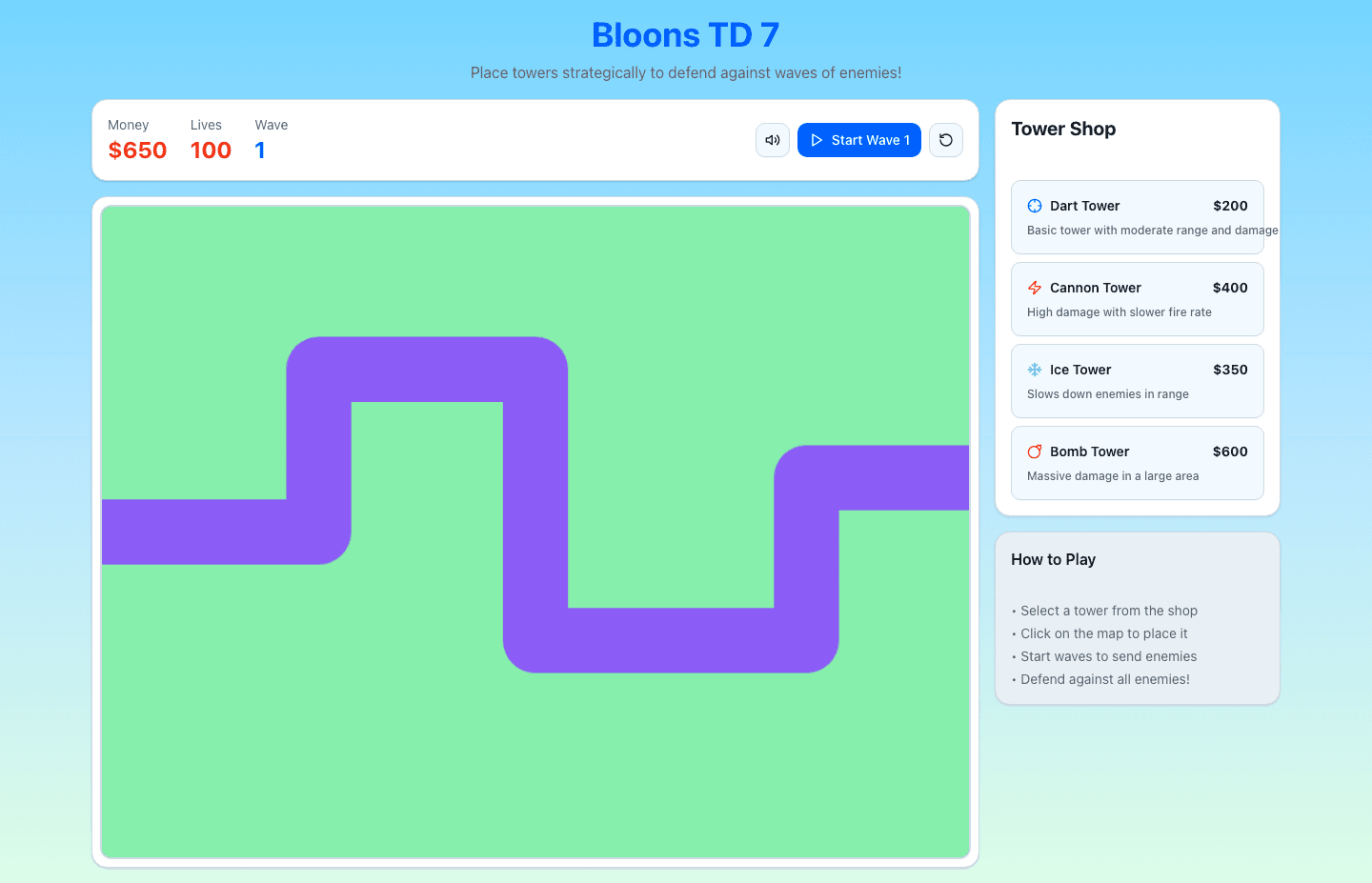

create an app called bloons td 7 and use the mechanics of bloons td 6

Then immediately:

the towers are not attacking and the bloons are supposed to go on the track

From there it looks like a real product loop: fix the core mechanic, add upgrades, add content, balance it, polish it, and then:

Make it so you can play on mobile

The surprising part isn’t that he can ask for it. It’s that he keeps coming back until it’s playable.

This arc is about fidelity. He wasn’t trying to generate a story — he was trying to generate the right kind of story with the right look.

He kept pushing on the same nerve:

Make it more gumball and not something else

And when it got it wrong:

STOP MAKING DARWIN HAVE A BODY HES A GOLDFISH

This is what “prompting” really means for normal people: repeated attempts to get the system to match the picture in your head.

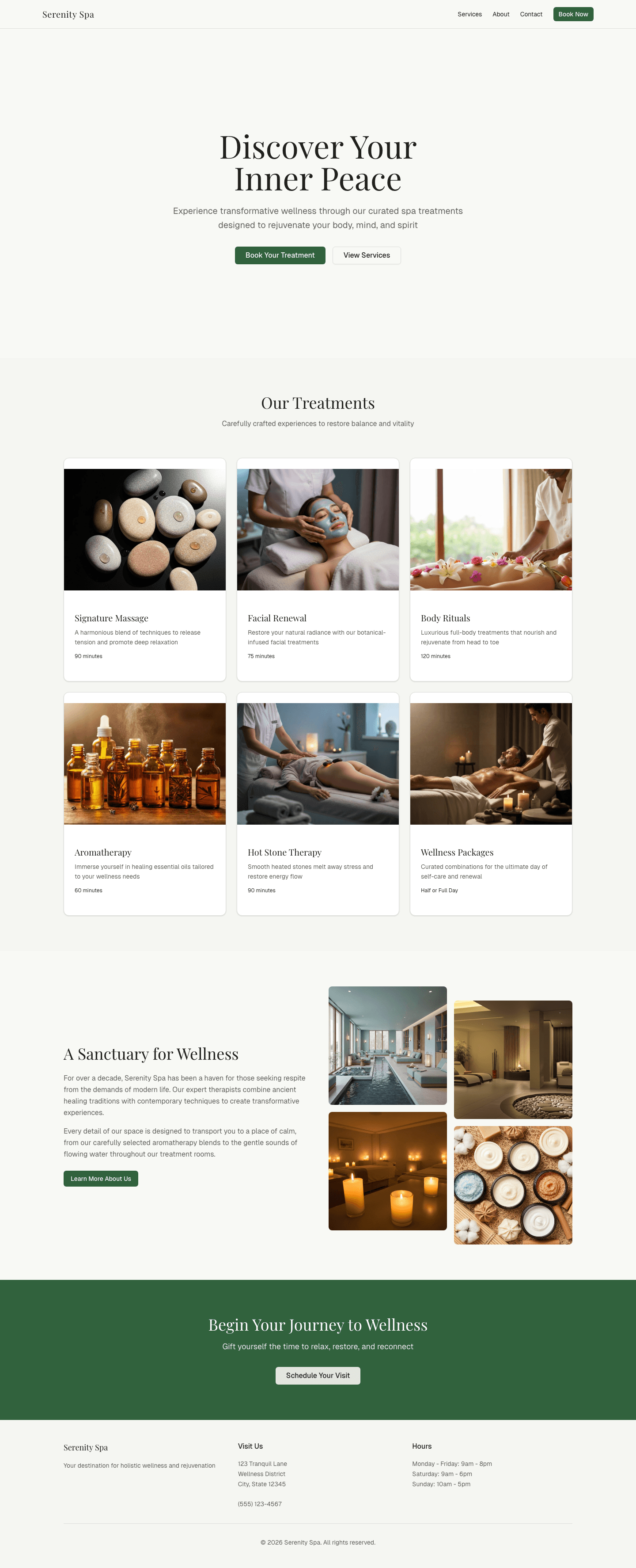

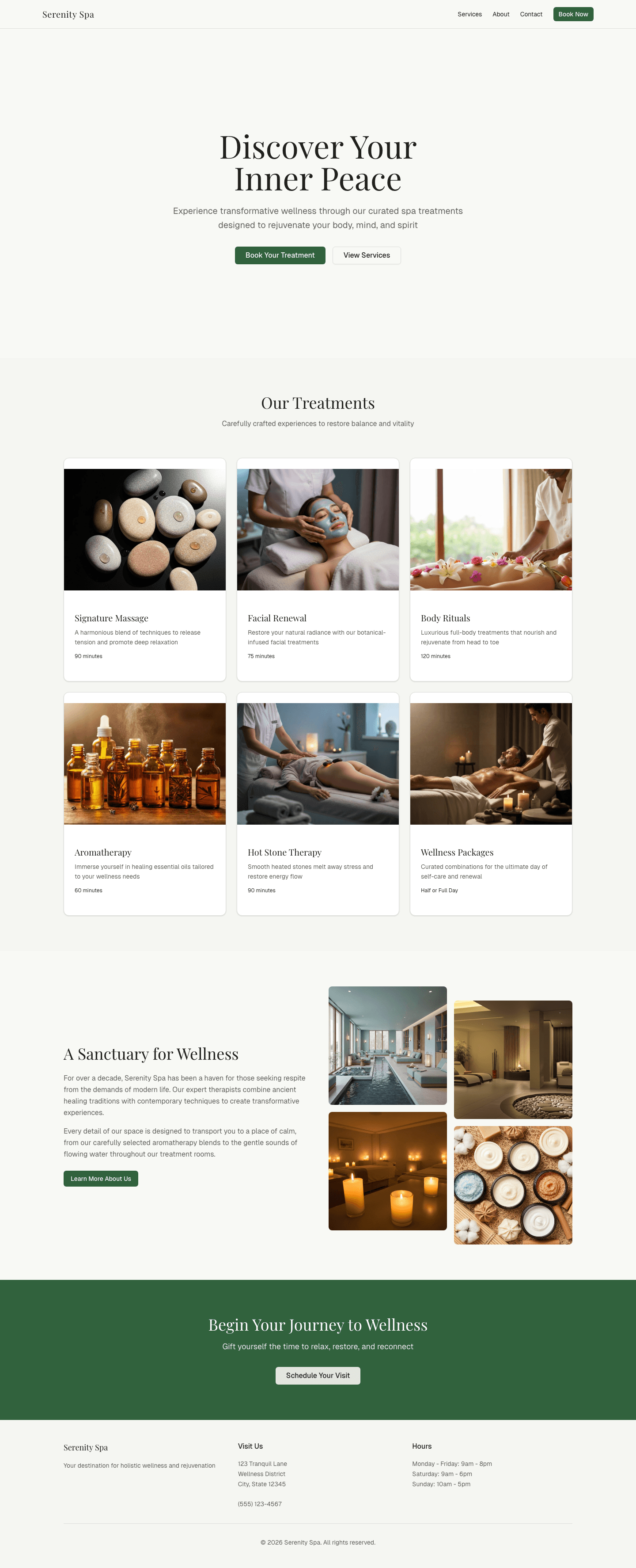

This one started as pure pretend-play (a spa with his sister) and quickly turned into a real product spec:

That’s a seven-year-old doing real software product work: defining requirements, iterating on them, and feeling when the last mile isn’t done yet.

A spa website Max built with booking + reviews + admin concepts, iterated over 26 prompts.

He didn’t ask for an app. He asked for a world:

When adults talk about “platforms,” kids just ask for them directly.

This one didn’t even load: a broken import on the shared demo.

This one didn’t even load: a broken import on the shared demo.

These were rare, but they matter:

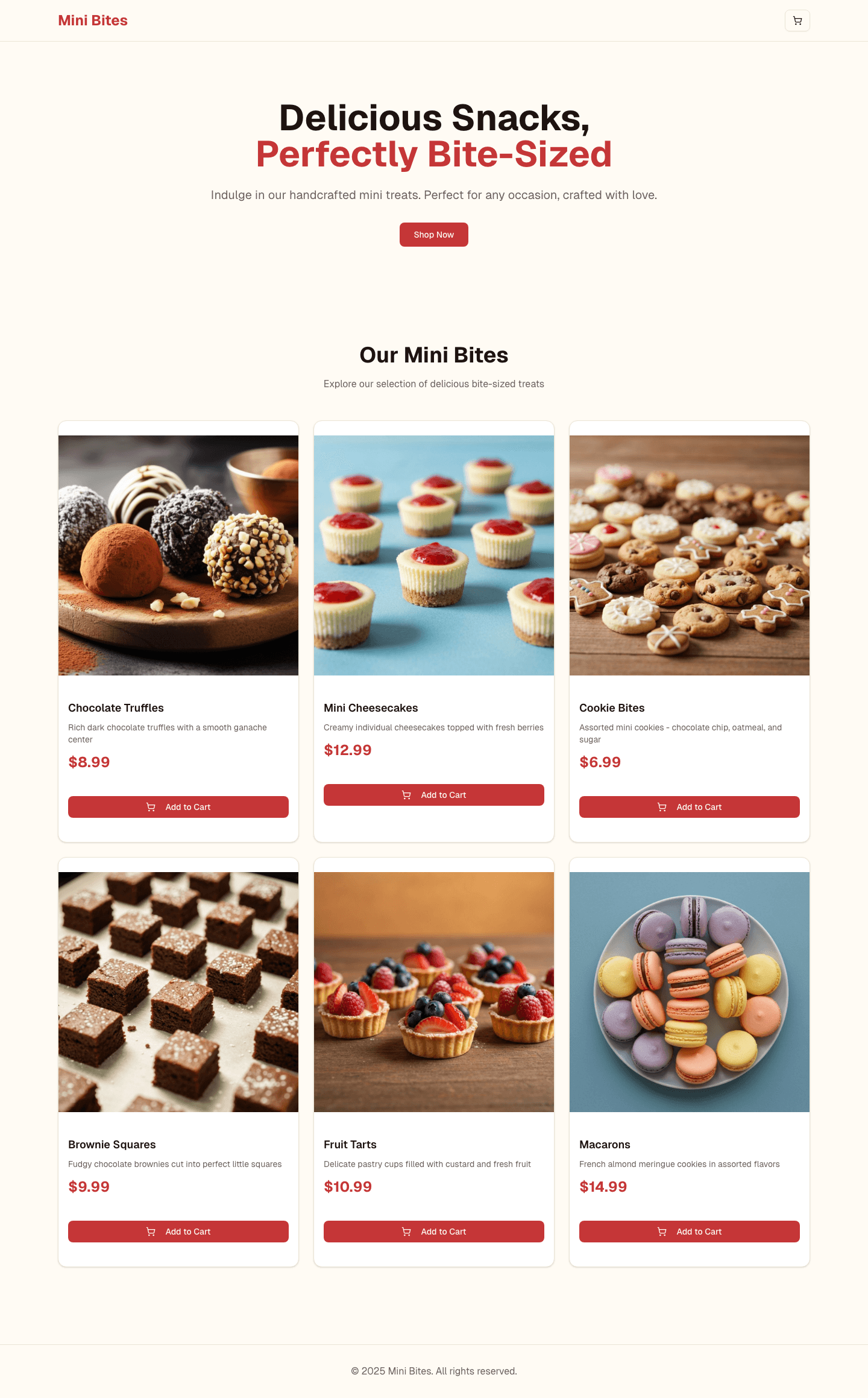

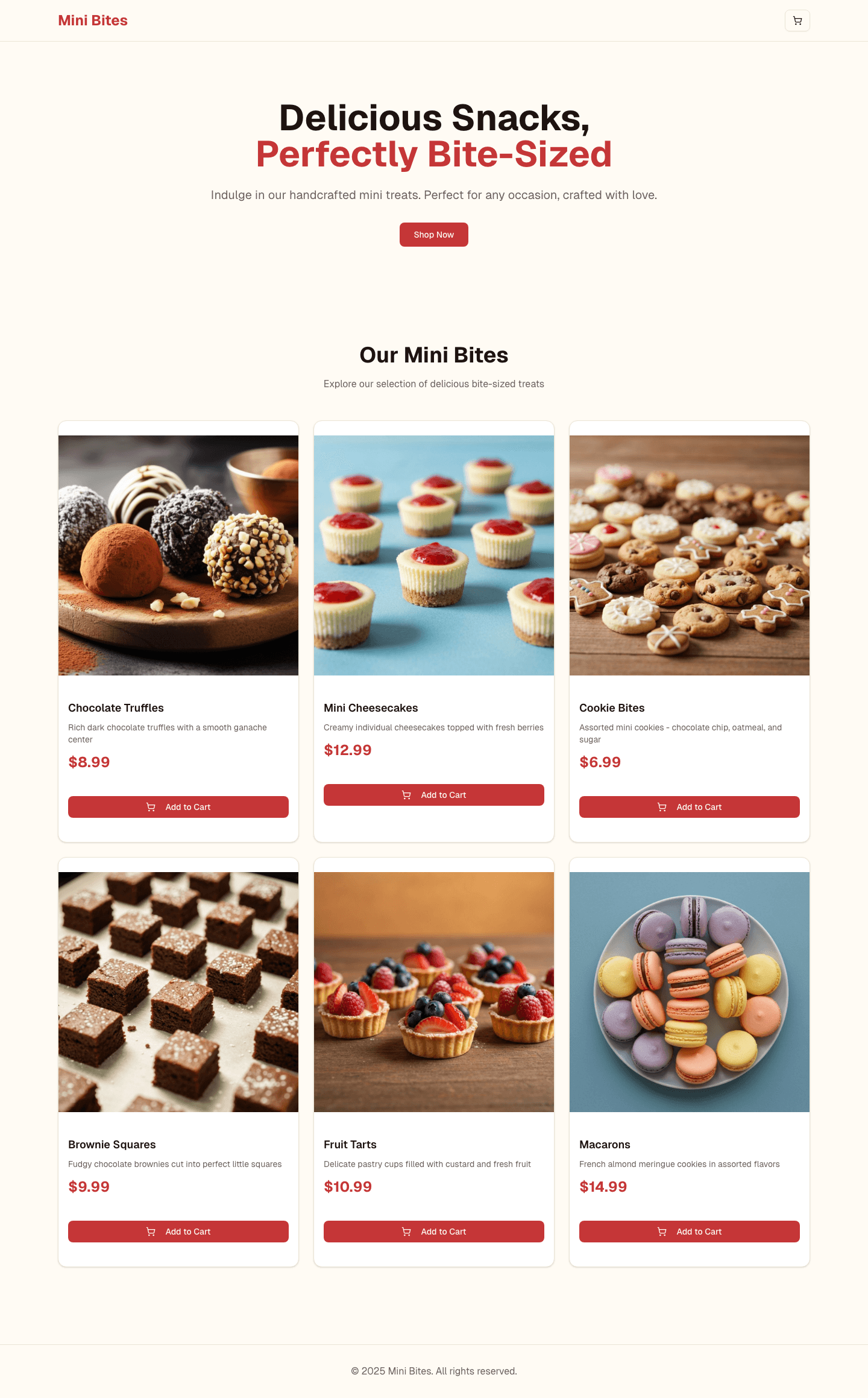

None of this was connected to real payment rails, but it’s the first time I’ve felt a new kind of parenting weirdness: a kid can generate something that looks like commerce by accident.

A “store” UI built in 10 prompts. Looks real enough that you’d want guardrails before publishing.

Max isn’t “learning to code” in the way I learned to code.

He’s learning something else: how to get a computer to produce a specific experience, and how to iterate until it matches the thing in his head.

That’s personal software in its purest form: you want a thing to exist, so you make it, then you live inside it.

I’ve been calling this broader shape the Disposable Intelligence Era: the cost of creating (and discarding) software is collapsing, so the scarce part becomes taste, direction, and iteration.

Max isn’t learning React. He’s learning the loop: imagine → specify → judge → iterate → ship.

When these tools start remembering context (mobile, style, preferences) across chats, the real unlock isn’t “write code faster.” It’s that a kid can grow a persistent world over weeks — and actually live inside it.